The Outsider, The Self-Made:The Universe of Helen Martins

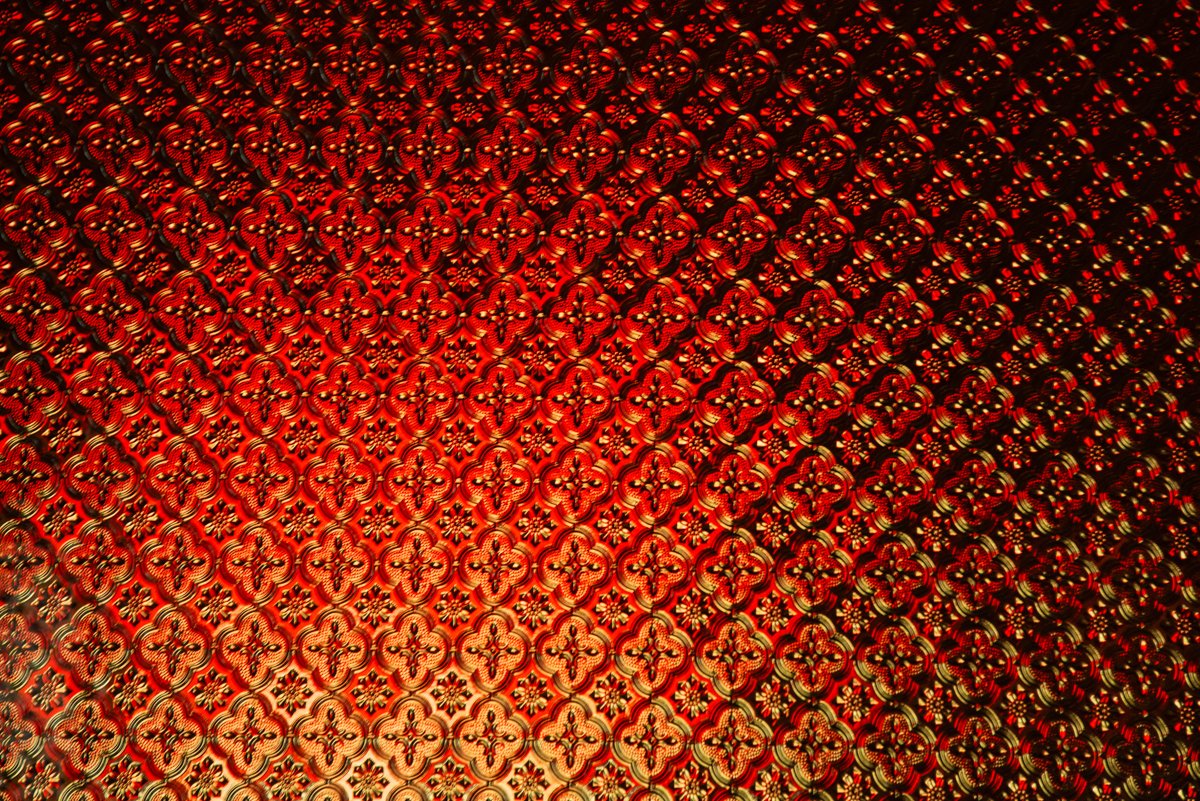

There is a sky of splintered glass above, signalling the end of day.

Coruscating green angled against a lilac softness, black glittering separating the red gems of walls and ceilings masquerading as that of semi-precious.

A tall man walks into the room with his wife. British tourists in their sixties.

The experience of being able to walk straight into the mind of a visionary whose mind borders on the hallucinogenic has him visibly perturbed.

"What do you think of this?" he demands.

I express admiration; he responds with further disbelief.

This house of kaleidoscopic attack is exactly that; arresting, disarming. Your eyes may try to focus on each signature, but you are overwhelmed and in this state of being flustered, it is perhaps easier to seek a standardised solution. Madness, depression, eccentricity: to sum up the indecipherable to malady.

Helen Martins, as with a myriad of fellow artists scattered across oceans and eras, would not be immune to this summation.

A temple sitting squarely in a dusty village named Nieu-Bethesda.

With dusty as a lathering of one’s skin in a viscous lava of grime as particles meets sweat induced from a boiling sun.

The avenues are lined with imposing willows, the brilliance of their curtains turned muted as the yellow sand of the Karoo whips white walls a uniform shade.

The Dutch Reformed Church's urge to add another place of worship to the roster was what led to the forming of this village in 1878. Initially, a farm owned by B.J. Pienaar, it was known as 'Uitkyk,' translated from Afrikaans as 'Look Out,' a literal reference to the local farmers having to be cautious of the San whose land they had claimed ownership of. Merging municipality and church, citizens were obliged to pay a double tax, and this, among larger economic triggers such as The Great Depression, led to the village losing the majority of its population and potential in acquiring the status of a grand Eastern Cape town. Indeed, it is sleepy - nightmarish once night falls and a blackness like no other envelops its streets. The NG Kerk tolls its bells, as it has done for centuries, and children from the Pienaarsig township, a band of residences circling the perimeter of the town, dance along and push stick to soil in boredom.

Time turns fluid.

An internal racing slows down, and thoughts are allowed to wander aimlessly. It appears it was in this state of flux that a thirty-something-year-old Helen Martins found herself in.

Returning home after a failed marriage to dramatist Johannes Pienaar, she assumed the proverbial role of feminine caregiver to her debilitated parents. She was the youngest of six children. Her mother, her ally, died in 1941 from breast cancer. Her father, described as somewhat of an Old Testament-doused monster of cruelty, died in 1945 from stomach cancer. The latter was moved to a room etched with the name 'The Lion's Den,' where the windows were boarded up, and walls adorned with black glass. Entering the den, a defiance is palpable - more so than the imagined imagery of a sickly man being confined to isolation. Apparently, he was not spoken to at all in the last years of his life and this seemingly harsh sentence was served as a final act of revenge.

For those who know small towns, there is an innate understanding of fenced whisperings and Bible-belted condemnations. For Helen Martins, a divorced woman hell-bent on creating her own mystical world, a small place such as Nieu-Bethesda was both a cage and a paradise.

The Owl House, on Martins Street, is an inconspicuous structure.

A pilgrimage of cement figures - Biblical and mythological - move towards the East in the courtyard.

Wise men, giraffes, sphinxes, back-bending figures complete with coloured glass punctured attire mark The Camel Yard, a personal mecca of Martins. And, of course, there are owls. Omnipresent guardians. Bearers of intuition and self-actualisation within Western culture; harbingers of death within local African culture. You feel their glazed eyes resting upon you as you circle the perimeter of the garden.

A sign hangs above a fence: 'This is my world’.

This space of evident pride allowed her creative direction to grow and fostered collaborations with local craftsmen. Jonas Adams, Piet van der Merwe and Koos Malgas (her longest collaborator at twelve years and a remarkable sculptor) were local coloured construction builders and sheep shearers whom at various points of their lives entered Helen's orbit. Without their understanding of materials and construction techniques, her works would have never materialised. According to locals, she was aware of how crucial their mastery was to her creative vision and would pay them above the going rate. This, coupled with them being a handful of people to access Martins' property, soon resulted in further kindling to the local rumour fire.

A promiscuous woman of no morals.

A witch who cast spells via her statues.

A traitor to the local Afrikaans community; one who blatantly disregarded the social rule of staying away from a community limited to living on the outskirts.

This ostracism would set the path in Helen fully embracing her outsider art.

Her days were occupied with transforming her house and garden. She rarely partook in the production, part for grinding beer bottles in a coffee grinder and these bean-sized glass results would line the interior walls and ceilings of The Owl House, allowing vibrance to embrace each room.

The pantry is abundant with jars of these grindings.

A candy store of fluorescence waiting to be plastered on yet another wall. Other walls were knocked down to force more light between the rooms with the addition of custom-shaped mirrors to further reflect the adjoining rooms' vivid walls. This obsession with luminance is tangibly tied in with a kitsch sense of humour. A lime precursor to the Furby stands wide-eyed in front of a framed nude in her bedroom. A sickle moon mirror doubles the painting of a praying Joan of Arc (flanked by a background of lions) in the dining room.

The guest bedroom's one single bed - dubbed The Honeymoon Suite - is occupied by a white and black doll lying alongside one another as a country outside wages a racial divide. They are overseen by a cross fashioned out of a mirror. Standing before this somewhat odd scene, you catch your reflection in that symbol so ironically synonymous with both love and rebuke.

I have read burdensome descriptions of these household features in articles.

Frightening, menacing, shocking, evil. None of them seems to fit.

There is a playfulness, a leaning towards the satirical, that underlines placement and choice. It's as if she were there in the room with you, all of her seeping into each strategically placed item and artwork. A tiny figure lies on the floor in the green room. Its body and head concealed with a leather bag, only one foot and one hoof protruding as evidence of form. The Little Devil, she called it. And in the dining room, against a sun-yellow wall, there's a hand-coloured photograph of a Voortrekker woman, white bonnet complete, smiling with the Pretoria Voortrekker monument looming behind her. Heritage, spirituality (avoiding overtly religious as it seems to be more personalised than straight-cut), mythology, and romance weave this house together.

Helen would make her way through each room to enjoy the moving light and set-up scenes, planning more 'work'.

Never 'art', but 'work'. That term succinctly encapsulates a necessity to express, to negotiate a physical space that was lagging behind. Now we exit the house through a small door between the kitchen and bathroom. The numerous statues captured in a moment of journey are still frozen. Their eyes have changed with the passing of heavy clouds. They face towards the monumental Sneeuberg mountain range. The splintering sun of the morning has given way to an ominous sky, promising a rainfall that would be so welcomed in this land of the dry. To the left of the property, across the street, resident craftsmen selling quintessential Owl House sculptures showcase their works under battered tarpaulin and corrugated iron. I am told several of them are direct descendants of Malgas and Adams. Calling out sales pitches with promises of discounted prices, their individual artistry is evident in the slight characteristics that make each owl, and sun, and camel, and cross. I purchase three owls and one misshapen star that sways overly to the left, its asymmetry marking a particular beauty.

The total amounts to R180.

Times have been tough.

This recession. Tourists no longer venture out to this small village. Petrol prices have increased.

Down the road, a Dutch-style house is going for R3,500,000.00, formerly owned by a Johannesburg finance big-shot.

It will definitely sell, we are told. It's a cute getaway to remove oneself from the chaos of the city.

A cage and a paradise of a village of a country of a world that seesaws between extremes of experience as a birthright.

Helen Martins falls in here, with all the rest of it.

She took her own life at the age of 78 by ingesting caustic soda. Those closest to her share letters of her expressing her loneliness and disillusionment. Her eyesight was slipping, and her church of shine was fading right before her. There seems to be a common thread in written accounts that her solitary life of creation was what lead to her inevitable downfall. A quick reasoning to determine her depression. But perhaps she was just another person who aged, and as with all those who must lose their links to vitality, there is also a loss of willingness to go on once this sense of purpose has been cut. We know those individuals. The grocery store owner who can no longer count the fruit and stand proudly by the counter. The dancer perfecting a dance notation for decades whose limbs decide to turn calcified.

There is a cruel yet imperative cycle to this mortality game.

However, in a classroom in some other dusty town in 2006, there were students who would look at glossy imagery of The Owl House and The Camel Yard. They would trace the outlines of the ceilings covered in glass with their fingers, almost feeling the grittiness to touch, relishing in the visuals of a world that seemed brilliantly removed from the known and the common. And a decade and a half later, they would make the trek to Nieu-Bethesda specifically to see this universe of Helen Martins.

And that alone surpasses any and all summations.